I have recently gathered a talented team of contributors for ToriAvey.com. I look forward to sharing their writing with you. Michael W. Twitty joins the team to explore African American and Southern foodways. Read more here. ~ Tori

—

“It’s slimy,” people often say without thinking when you first bring up the topic of okra. Yes, okra is mucilaginous (the technical term for slimy), and no, it isn’t only good fried, as many people attest. Okra is actually a very versatile fresh, crisp vegetable that has a bad rap. The genus Abelmoschus has several cultivated species, but the one that crossed the Atlantic sometime in the sixteenth century was Abelmoschus esculentum. Related to cotton and other mallow family plants, okra is an ancient vegetable that originated in southern Ethiopia in far antiquity. It provides thickness and savor in the one-pot stews that are the basis of many traditional African diets.

Spreading across to Western Africa and down into the central part of the continent during the Bantu migrations around 2,000 BCE, okra has been a staple in African and African diaspora cuisine for a long time. It even crossed the ocean to Asia at an early date and spread with Islam to India, where it is called “ladies fingers.” About the same time okra was making its appearance in Brazil, the West Indies and later mainland North America, it made its way to China and the island of Macau where it bears one of its many African names—quilobo—from Angola. In fact, quilobo is one variant of the KiMbundu word quingombo, where we get the word “gumbo. From the Igbo language of southeastern Nigeria we get the vegetable’s English name, as okwuru became ochra and okra. Along the entire length of the 3,500 mile coast exploited by the trans-Atlantic slave trade, okra was grown and cooked with other vegetables or rice and made into soup.

Slave traders had a knack for studying and recording the lifeways of the African ethnic groups they sought through war and kidnapping. The ample primary sources that read as early ethnographies were really guides to inform contemporary traders about the ups and downs and ins and outs of enslaving and exporting specific ethnic groups and Africans from distinct regions. Understanding the food of the people you were enslaving was critical; it ensured they would be well fed on the perilous Middle Passage and when they arrived in the New World. Since most of the early trade went directly to cognate tropical areas on the other side of the ocean, a concerted effort was made to bring familiar food crops along that enslaved Africans could plant to remind them of home. Cruel a business as the slave trade was, it was still recognized that culinary homesickness was a great deterrent to the “seasoning” process.

In mainland North America, okra was one of the ultimate symbols of the establishment of the enslaved community as a culinary outpost of West Africa. Noted in Brazil in the 1500’s and in the West Indies throughout the 1600’s, okra was a relative latecomer to colonial America. Our best guess is that it came here at the start of the 18th century. Charleston and New Orleans were early hotbeds of okra cookery for certain, but okra was not confined to the Caribbean outposts of the Old South. Peter Kalm discussed okra in his American travels as a popular plant for soups among blacks and whites in the 1740’s. Thomas Jefferson lauded it as one of Virginia’s esteemed garden plants in the 1780’s, and references to okra can be found in garden records and maps across the early Mid-Atlantic, Chesapeake and Lower South.

For enslaved cooks, okra was a common thread in their mixed African heritage. To the Wolof people it was kanja, to the Mandingo, kanjo, to the Akan it was nkruman and to the Fon, fevi. Okra was most often prepared in a peppery stew that was eaten with rice, millet, hominy or corn mush. It was boiled with onions and tomatoes in a saucy preparation that was eaten in the same manner, or it was boiled on its own as a fresh vegetable. Okra with rice was called “limpin’ Susan,” the cousin dish to cowpeas and rice, or “Hoppin’ John.” It was also boiled up with cowpeas for another dish, fried in small pieces with the boiled leaves served as a leafy green.

Okra soups became signature and staple dishes throughout the South. It is hard to know where the family tree starts and where it stops. Some varieties of Kentucky burgoo and the Brunswick stew of the Southeastern coast contain bits of okra thrown in with the usual mix of tomatoes, onions and hot pepper. Okra soup thick with crab became Baltimore’s “crab gumbo” and Charleston and Savannah’s “rouxless gumbo,” while in New Orleans the roux made okra soup even thicker. Summer Louisiana gumbo came to mean okra gumbo flavored with chicken, seafood or whatever the seasons allowed. From Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife and her “ochra soup,” to Lettice Bryan’s The Kentucky Housewife, Sarah Rutledge’s The Carolina Housewife and Mrs. B.C. Howard’s Fifty Years in a Maryland Kitchen, it is clear okra dishes passed from the hands of enslaved cooks into those of literate white ladies. These cookbook authors published their favorite versions, leaving us records of regional variations on this classic, ancient dish.

Here is a peppery, historically inspired recipe for Okra Soup. This version is based on recipes from the 19th century, especially those of Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife (1824) and Mrs. B.C. Howard’s Fifty Years in A Maryland Kitchen (1881 edition). This simple DIY heirloom recipe has a few modern updates. The culinary trinity of hot pepper, tomato, and okra served with rice reinforce this soup’s connection to similar dishes found from Senegal to Angola, and Philadelphia to Bahia.

Interesting fact: Enslaved African Americans grew okra and parched the seeds to make a fake version of “coffee.” During the Civil War, it was common to sell this brew to white soldiers, Confederate and Yankee.

Recipe Photography and Styling by Tori Avey

Recommended Products:

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Okra Soup

Ingredients

- 1/4 cup butter

- 1 tablespoon olive oil (lard would historically be used - we subbed olive oil to keep the recipe kosher and vegetarian)

- 1 small onion, diced and dusted with flour

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 2 tablespoons finely chopped flat leaf parsley

- 1 sprig fresh thyme

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon black pepper (or to taste)

- 1/2 teaspoon red pepper flakes

- 4 cups vegetable broth (chicken or beef broth can also be used - we used vegetable broth to keep the recipe kosher and vegetarian)

- 3 cups water

- 28 ounces canned tomatoes with juice (or 3 1/2 cups fresh tomatoes, peeled and diced)

- 2 cups fresh young okra cut into small, thin pieces, or frozen okra pieces

- 2 cups cooked rice, kept hot or warm (optional)

NOTES

Instructions

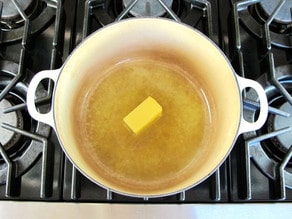

- In a Dutch oven, heat the butter and oil until melted.

- Add the onion and finely chopped parsley and gently cook until onion is translucent and soft. Add the garlic and cook for a minute more until fragrant.

- Add the thyme, salt, black pepper and red pepper flakes and cook for another minute or so.

- Add the broth, water and tomatoes and cook on a medium simmer for 30 minutes.

- Add the okra and cook for another 20-25 minutes, or until tender.

- Ladle into bowls over ¼ cup lump of warm rice each. Serve.

Nutrition

tried this recipe?

Let us know in the comments!

Research Sources

Carney, Judith and Richard Nicholas Rosomoff (2009). In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s botanical legacy in the Atlantic World. University of California Press. Berkeley, CA.

Grime, William E. (1979). Ethnobotany of the Black Americans. Reference Publications, Algonac, MI.

Hatch, Peter. (2012) “A Rich Spot of Earth”: Thomas Jefferson’s Revolutionary Garden at Monticello. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

For more information, check out Michael’s entry on okra in the Encyclopedia of the Material Life of Slaves in the United States (2010), Martha B. Katz-Hyman and Kym S. Rice, editors. Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA.

THK asks: Are you a fan of okra, or does the slimy texture make you squeamish?

I love this recipe! It’s one of my favorite soup recipes. Simple, savory, delicious! And a special thank you for the article about the history of okra. I tasted okra for the first time when I moved to the States (I’ve never had it or heard about it before). Now I’m back in my homeland of Russia and I’m happy I’m able to find frozen okra here. 🙂 Thanks again for the recipe!