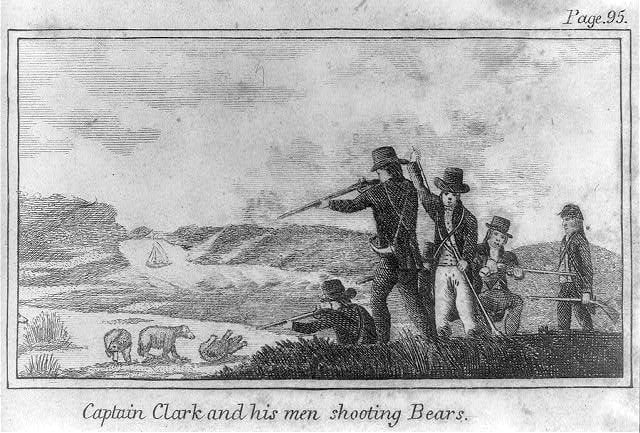

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Captain Meriwether Lewis and Lieutenant William Clark, better known as Lewis and Clark, led one of the most famous expeditions in American history. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson, the Corps of Discovery Expedition was one of the earliest exploratory missions to the Pacific Coast. Though its primary purpose was to find a direct water route to the Pacific Ocean, President Jefferson also wanted the journey to focus on the economic usefulness of different regions, particularly in terms of plant and animal life. On May 14, 1804, along with 31 other men, Lewis and Clark set out to do exactly that. It was a long, treacherous trip by water and on foot across a vast unknown wilderness. Keeping the expedition members healthy and well-fed was obviously a pressing concern. This epic mission had a wild, strange and often surprising menu.

The trek began with training at Camp Dubois near Hartford, Illinois and ended at Fort Clatsop near what is now Astoria, Oregon. Traveling across this massive distance required a lot of preparations. Lewis and Clark had to think ahead and plan for times when wild game would be unavailable or in short supply. Their keelboat was stocked with nearly 7 tons of dry goods, including flour, salt, coffee, pork, meal, corn, sugar, beans and lard. About 93 lbs of portable soup, a concoction that was boiled until gelatinous and then left to dry until hard, was also brought along. This was hardly a favorite meal, but it saved the men from starvation on more than one occasion.

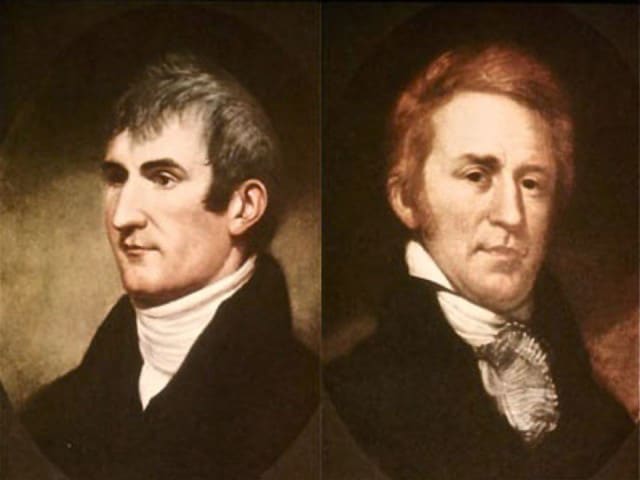

Captain Clark and his men shooting Bears. Source: Library of Congress.

To understand how difficult and physically demanding the Corps of Discovery Expedition was, you need only look at the amount of food they consumed. On July 13, 1805, Clark wrote: “We eat an emensity of meat; it requires 4 deer, or an elk and a deer, or one buffaloe to supply us plentifully 24 hours.” When wild game was plentiful, each man consumed up to 9 pounds of meat in one day. That’s a lot of protein! Meat was vital to their diet; it helped to fill their hungry bellies and gave them the strength required to pull canoes and carry heavy loads. The types of meat that were eaten also served as a reflection of the season, terrain and climate they encountered. Bison and deer were prominent during the crossing of the Great Plains, while salmon and a starchy tuber known as wapato kept them nourished as they entered territory west of the Rocky Mountains. Fish was eaten in abundance, a favorite being the eulachon, or candlefish, which Lewis claimed to be “superior to any fish” he had ever tasted. At Fort Clatsop, elk was in large supply. It was served boiled, dried and roasted for breakfast, lunch and dinner. At one point during their journey, Lewis, Clark and their fellow travelers extracted salt from seawater by way of evaporation through boiling. Salt was a flavor enhancer, but it was also essential in preserving meat. This was undoubtedly helpful in giving their perishable meat supply a longer shelf life.

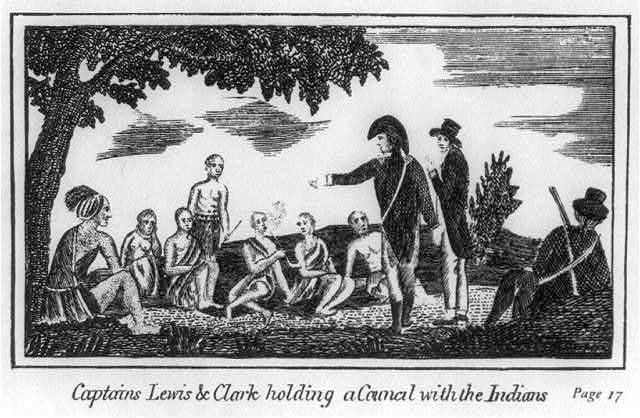

Captains Lewis and Clark holding a Council with the Indians. Source: Library of Congress.

The travelers replenished their food supply through hunting and gathering along the way. Tradable goods were brought along to use as gifts in exchange for help from Native American tribes. This proved to be a wise decision, and the Native Americans became an invaluable source when food was scarce. The Mandan tribe of North Dakota provided squash, beans and corn. The Chinook along Washington’s Columbia River gave them essential, energizing carbohydrates in the starchy wapato. When they reached their final destination at Fort Clatsop (near modern day Astoria, Oregon), the Clatsop tribe traded berries, wild licorice root and elk. As they passed through modern day North Dakota, French-Canadian fur trapper Toussaint Charbonneau joined the expedition with his wife Sacagawea, a young Native American woman from the Shoshone tribe. Sacagawea proved a valuable member of the team. She was able to identify edible plans and roots that the men had never seen before, including currants, wild licorice and wild onions.

The men took turns cooking meals. Oftentimes the available ingredients were new and unfamiliar, forcing the men to get creative. On June 5, 1805, their journals reveal that they had “burrowing squirrels” for dinner and found them “well flavored and tender.” At one point on the trail, Sacagawea’s husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, made a dish called boudin blanc. This sausage made from stuffed buffalo intestine impressed the hungry travelers. Periodically, Lewis rewarded his men with suet dumplings made from boiled buffalo meat. On August 14, 1805, in the midst of a food shortage, Lewis recalled a mixture of cooked flour and berries: “On this new-fashioned pudding four of us breakfasted, giving a pretty good allowance also to the chief who declared it the best thing he had tasted for a long time.” The dish sounds remarkably similar to a pandowdy or cobbler; an impressive culinary feat in the midst of a harsh trek through the wilderness. Forced into culinary creativity, members of the expedition foraged and hunted for a variety of new foods they had never tasted before. By the end of the journey, Lewis, Clark and the men of the expedition had eaten a wide variety of meat, fish, berries, vegetables, fruits and roots. These simple native foods ultimately fueled the most famous expedition in U.S. history.

Research Sources:

Ambrose, Stephen (1997). Undaunted Courage. Simon & Schuster, New York, NY.

Huser, Verne (2004). On the River with Lewis and Clark. Texas A & M University Press.

“The Journals of Lewis and Clark.” University of Virginia, n.d. Web. 2 May 2013.

Mansfield, Leslie (2002). The Lewis and Clark Cookbook. Celestial Arts, Berkeley, CA.

Ronda, James P. (1998). Voyages of Discovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Montana Historical Society Press, Helena, MT.

Woodger, Elin and Brandon Toropov (2004). Encyclopedia of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Facts on File, New York, NY.

They ate almost as many dogs as they did bison. I feel it should be mentioned. If not on the merits of quantity consumed then on the importance of the morale that eating dog flesh created. In the Pacific Northwest, having animal flesh on the dinner table once again – at that point – was very pleasing to them after day after day of fish and roots. This is an informative article, definitely in my L&C bookmarks, thanks.

Great post! So very interesting and I also have been facinated by this piece of history especially of late. Thanks for sharing.

This is an interesting look at an element of the expedition not often considered. Thank you for sharing.

Glad you enjoyed it Jody 🙂

Fascinating and thanks for this amazing info!

bjmcmanus

They apparently ate a high fat diet, not much grains (only when they could not get other foods), and tons of saturated fat

This is incomplete. The Expedition got sick off salmon and finally refused to eat it. More than once the Expedition was saved from starvation by bartering for the Indians dogs which they ate with relish.

Interesting facts, thank you for sharing. I did mention salmon and fish in general as a major dietary source, and I also dedicated a paragraph to bartering with the Native Americans for food. Please note that this post was meant to be a summary overview of their diet on the trail, not a detailed rundown of every single item they ate (or got sick of) on their journey.

really interesting article. thanks

Glad you enjoyed it Vince! I’ve been fascinated by Lewis and Clark for a few years now; caught the bug from my dad after he read “Undaunted Courage.”

Lewis and Clark shot so many animals for food that they left shortages for the local natives. As Lewis and Clark reached the Shoshone and Nezperce camps in the Rockies, they themselves were starving, and had to rely on hand outs from natives who were also starving. Check it out in this Google Map of the Lewis and Clark expedition where you can read their actual journals entries as you trace their journey.

That map is terrific, PS, Thanks for sharing! The journals are available in several locations online, but I’ve never seen an interactive map like this. Very cool.

Twenty four white men decimated the wildlife n left the local indigenous population starving. You have to be kidding. Oh, or wait you have that written, video testimony to prove it.

They did a lot of of questionable things but wiping out the wildlife was not one.

Wake up

Enph,

Actually yes. Your comment indicates that you never actually read the daily accounts in Lewis and Clark’s own journal. It is in Lewis and Clark’s own journal about how many animals they killed, and it is in Lewis and Clark’s own journal about how when the came upon native villages how the natives were starving. And it is in Lewis and Clark’s own journal about how the Nez Pierce shared with Lewis and Clark what little they had.

Comments like this:

(4/21/1805) “We saw immence herds of buffaloe Elk deer & Antelopes. Capt Clark killed a buffaloe and 4 deer in the course of his walk today; and the party with me killed 3 deer, 2 beaver, and 4 buffaloe calves…”

(5/10/1805)’…The hunters returned this evening having seen no tents or Indians nor any fresh sign of them; they killed two Mule deer, one common fallow or longtailed deer, 2 Buffaloe and 5 beaver, and saw several deer of the Mule kind of immence size, and also three of the Bighorned anamals. from the appearance of the Mule deer and the bighorned anamals we beleive ourselves fast approaching a hilly or mountainous country…”

When you add up such comments over a period of time, they killed a a large number of animals, large enough to affect the local food supply during the winter months and is one of the reasons some of the tribes feared Lewis and Clark’s travel through their territory.

The MyReadingMapped map of the Lewis and Clark Expedition has been moved to a new site at http://climateviewer.org/index.html?layersOn=mrm-79