Jane Austen wrote what she knew. She was raised as a member of the landed gentry, a British social class made up of landowners who lived off the income they received from renting their land. Austen’s plots reflect real quandaries and concerns of the time period; because of this, readers related to the characters and situations presented in her novels. Her characters were based on her peers, her family, her neighbors. Here on The History Kitchen, I find myself wondering what it was like to dine with Jane Austen and her contemporaries?

During her short life from 1775 – 1817, Austen became accustomed to a lifestyle in which the day’s events were divided by meals. Everything was carefully organized, from the order in which people were seated to after dinner activities. Naturally, this lifestyle and way of eating is featured prominently in Jane’s novels. Unfortunately for food lovers, there are very few references to specific dishes or recipes in her work. Though the actual food may not have been described in detail, the social aspect of mealtimes resounded loud and clear.

The men and women of Austen’s era typically began their day tending to any important business or shopping. At around 10am, the family would sit down to a long breakfast that extended from morning well into the afternoon. Jane made breakfast for her family every morning. This meal always included tea, which is given a lot of attention in her novels. At the time tea was very expensive; it was imported under a virtual monopoly from China by the East India Company. to have tea was indicative of a family’s social status. If a family was able to offer tea to guests, it was assumed they were of a high social status. In Jane’s household tea was so highly esteemed that it was kept in a locked cupboard to which Jane had the only key.

Jane Austen, 1873. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Each of Austen’s novels includes a significant scene in which tea is involved. Author Kim Wilson points out several of these moments in her book Tea with Jane Austen. “In Sense and Sensibility, what is everyone drinking when Elinor notices Edward’s mysterious ring set with a lock of hair? Tea of course. And in Pride and Prejudice, what is one of the supreme honours Mr. Collins can envision Lady Catherine bestowing on Elizabeth Bennet and her friends? Why, drinking tea with her, naturally.”

Dinner was the major event of each day. At around 4 pm, any invited dinner guests would arrive. The most senior lady was always seated first by the host who would then sit across from the hostess, followed by the rest of the guests who sat themselves in a descending order of seniority and importance. There were no placecards, which meant that young men might maneuver their way to sitting beside a young lady they desired. Children were dressed in their fanciest attire and presented to the guests before being escorted upstairs to have their own dinner in the nursery. After that, dinner was served. The meal was presented in two separate courses. The word “course” had a much different meaning during the late 18th century than it does now. Most of us are familiar with courses being presented individually, beginning with soups and salads, followed by an entrée and then ending with dessert. For Jane Austen’s family and their guests, the first course was an impressive spread that covered the entire table and included anywhere from 5 to 25 separate items, depending on the occasion. The table was nearly always set with a salmon at one end and a turbot with smelt at the other. Fortunately, no one was expected to eat everything on the table, but rather to choose three or so of the items that they most preferred. For refreshments, wine, beer, ale, and soda water were offered. After the first course, the table was cleared and reset with an intermediate course of salad and cheese. This was then cleared and the table was once again spread with a large second course, resembling the first in size but featuring different items. Once everyone had eaten their fill the dessert was sent out, usually consisting of fruit and nuts or mincemeats with ice cream. The children would often come back downstairs to enjoy dessert with their family before returning to the nursery for bed.

With a meal of that size, it’s easier to understand why the day revolved around it! How was there time for anything else?

Once the meal was complete, the men would continue to sit, drink and discuss while the ladies would excuse themselves to the drawing room to socialize over knitting or picture books before having tea or coffee. An hour or so later the men would join them and they would set off on their after dinner activities. In the summer this usually meant strolling through the grounds or, in the winter, playing cards or dancing in the drawing room.

This was the normal way of eating until around 1815, after Waterloo, when the English began to travel abroad again. Throughout Europe it had become the fashion to serve meals à la Russe, or “in the Russian style,” meaning they were plated beforehand and brought out to the table as individual courses. Upon returning to England, the chicest upper class residents began to implement this new style of dining in their households. If you watch Downton Abbey, this is the service provided for the family at mealtimes. Service à la Russe is the basis for how most Western restaurants serve meals today, where courses are brought to the table and served sequentially. Of course, the pomp and circumstance of true service à la Russe has long fallen by the wayside in the majority of establishments.

During Jane Austen’s time, printed recipes and modern cookbooks were not common. Without the convenience of simply taking a book off the shelf, women compiled their own collections of recipes that were handed down through the generations. If a woman took pride in her recipe for game pie, she would be sure to pass it on to the next generation. Because of this, some families became famous for their signature household dishes. In fact, Jane Austen’s family friend Martha Lloyd, who lived with Jane for several years, recorded many Austen family recipes in her recipe diary known as her ‘Household Book.’ Jane Austen scholar Deidre Le Faye referenced Lloyd’s recipes while compiling The Jane Austen Cookbook, a terrific recipe resource for history buffs and fans of Jane Austen.

In searching for a Jane Austen-inspired recipe, I looked to one of the few references to food in her novels– a silly (and seemingly never-ending) monologue in Emma wherein Miss Bates describes serving baked apples to Frank Churchill:

And when I brought out the baked apples from the closet, and hoped our friends would be so very obliging as to take some, ‘Oh!’ said he, directly, ‘there is nothing in the way of fruit half so good, and these are the finest looking home-baked apples I ever saw in my life.’ That, you know, was so very — And I am sure, by his manner, it was no compliment. Indeed they are very delightful apples, and Mrs. Wallis does them full justice — only we do not have them baked more than twice, and Mr. Woodhouse made us promise to have them done three times — but Miss Woodhouse will be so good as not to mention it.

While the apples Miss Bates describes are likely baked whole apples rather than a pastry, the closest I could find in Martha Lloyd’s Household Book was a recipe for Apple Puffs. Thanks to Maggie Black, Deidre Le Faye’s co-author in The Jane Austen Cookbook, I was provided a modern adaptation of the recipe. I adapted it slightly to better reflect the original text:

Pare the fruit, and either stew them in a stone jar on a hot heart, or bake them. When cold, mix the pulp of the apple with sugar and lemon-peel shred fine, taking as little of the apple juice as you can. Bake them in a thin paste in a quick oven; a quarter of an hour will do them if small. Orange or quince marmalade, is a great improvement. Cinnamon pounded, or orange-flower water in change.

I imagine these might have been served with tea in the afternoon, or perhaps as part of the breakfast spread with scrambled or poached eggs. It’s a simple and delightful recipe that I know you’ll enjoy. Brew a cup of tea, curl up in a corner with Emma, and treat yourself to a Jane Austen-inspired Apple Puff!

Recommended Products:

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Jane Austen Apple Puffs

Ingredients

- 8 ounces puff pastry

- 1 pound cooking apples - I used Granny Smith

- 1/2 cup water

- 2 tablespoons brown sugar

- 1 teaspoon lemon rind, finely grated

- 1 tablespoon orange blossom water or 1/2 tsp cinnamon (optional)

- 1 tablespoon fine-cut orange marmalade, plus more for topping

- Caster sugar for sprinkling

NOTES

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 400 degrees F. Grease and flour a baking sheet, or cover with parchment or a silicone baking sheet. Peel, core and slice the apples. Stew them in 1/2 cup of water until tender. Drain well and reserve the cooking juice. Allow to cool completely.

- Put the cooked apple in a bowl and mix in brown sugar, lemon rind, marmalade and optional orange blossom water or cinnamon. Taste and adjust flavoring as needed.

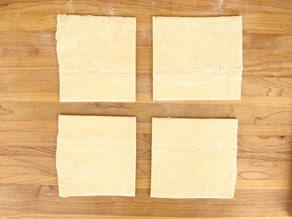

- On a lightly floured surface, roll out the pastry to 1/8 inch thick and cut the pastry into 8 4-inch squares.

- Divide the apple puree between them, placing it in a line across the center of each square and stopping well short of the ends.

- With a pastry brush, use the reserved apple cooking liquid to dampen the edges of the pastry.

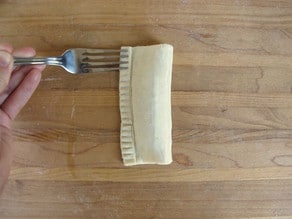

- Fold the two edges parallel with the line of filling over the puree. Pinch and seal the edges together with a fork, forming a tube.

- Pinch and seal the ends of the tube together and use a fork to seal shut.

- Brush the pastry lightly with the reserved apple cooking liquid and sprinkle with caster sugar.

- Using a sharp knife, gently cut vents into the top of the pastries.

- Place the puffs on the greased or lined baking sheet and bake for 20 - 25 minutes, or until golden brown.

- Serve warm, topped with a little extra marmalade or candied orange peel.

Nutrition

tried this recipe?

Let us know in the comments!

Research Sources

Black, Maggie, and Deirdre Le Faye (1995). The Jane Austen Cookbook. The British Museum Press, UK.

Olsen, Kirstin (2005). Cooking with Jane Austen. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT.

Pool, Daniel (1994). What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew. Touchstone, Simon & Schuster, New York.

Wilson, Kim (2011). Tea with Jane Austen. Frances Lincoln Limited Publishers, London, UK.

Just grate as always! Thank you for the recipe . I love the way you cook food and tell us historical facts behind it.

Hi, Tori! Love your recipes and this one looks wonderful. I love Jane Austen. I want to serve these for Thanksgiving instead of apple pie. But in order to do that, I would want to make them ahead of time. Any idea what the best way to store them would be? Or will they get to soggy if I make them a day or two ahead of time?

Thank you Tori – I love English history and the recipes, traditions that go with it. I can’t wait to try this. It would make a nice ending to a Rosh Hashanah menu.

Can you serve these cold too? I am definitely going to try this recipe! Looks amazing!

Room temperature or warmed up is best. Enjoy!

I can’t wait to try It!!